Finding Your Roots

La Famiglia

Season 11 Episode 2 | 52m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

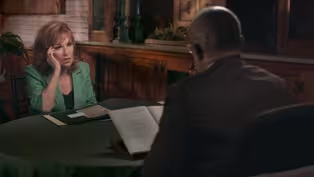

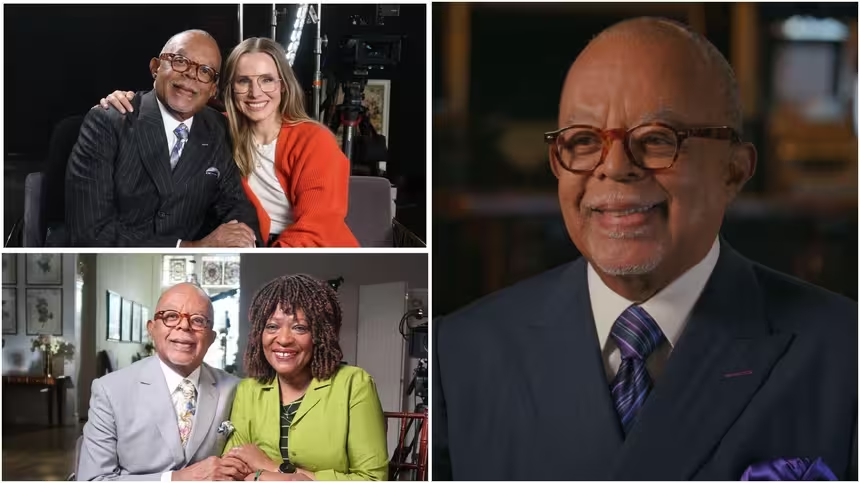

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the Italian roots of Joy Behar & Michael Imperioli.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the family trees of talk show host Joy Behar and actor Michael Imperioli—two Americans whose roots stretch back to small towns in Calabria, Italy. Joy and Michael’s families lived in these towns for centuries, but their stories were lost on the journey to America. Gates reveals the challenges that their ancestors faced—and overcame—on both sides of the Atlantic.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

La Famiglia

Season 11 Episode 2 | 52m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the family trees of talk show host Joy Behar and actor Michael Imperioli—two Americans whose roots stretch back to small towns in Calabria, Italy. Joy and Michael’s families lived in these towns for centuries, but their stories were lost on the journey to America. Gates reveals the challenges that their ancestors faced—and overcame—on both sides of the Atlantic.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Lewis Gates Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots."

In this episode, we'll meet talk show host, Joy Behar and actor Michael Imperioli, two Americans who are about to learn the secrets of their Italian ancestors.

BEHAR: I mean it's almost incestuous what we're talking about here.

GATES: You look out the window and there was an object of your desire.

BEHAR: Whoa.

IMPERIOLI: My grandmother must have known this story, but they, I guess this is not something they wanted to talk about.

Um, wow, that's so wild.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists comb through paper trails, stretching back hundreds of years while DNA experts utilize the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

BEHAR: Oh, look at that.

IMPERIOLI: I'd never heard this from anybody.

GATES: And we've compiled it all into a Book of Life, a record of everything we found.

BEHAR: Fourth great-grandparents.

GATES: They are your great-great-great-great grandparents.

BEHAR: Wow.

GATES: And a window to the hidden past.

IMPERIOLI: It's kind of incredible.

It's almost like, you know, the ghosts... GATES: Yeah.

IMPERIOLI: Of, of the family, it's very moving.

BEHAR: They're schlepping, they're walking miles and miles and miles.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: This is what people do to get out of poverty.

GATES: Both Joy and Michael descend from Italian ancestors who came to America with little more than the clothing on their backs.

In this episode, they'll explore the sacrifices those ancestors made on both sides of the Atlantic and discover family bonds that run much deeper and much stronger than they ever could have imagined.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ (book closes).

♪ ♪ (street noise).

(camera shuttering).

GATES: Joy Behar is utterly fearless, as a co-host of "The View," America's number one daytime talk show, Joy is willing to say anything to anyone.

A trait that is earned her legions of admirers, as well as a few enemies... CONWAY: Many people in charge... BEHAR: I like you... CONWAY: Well thank you, I like you too.

BEHAR: I think that right here you're being delusional.

GATES: But to hear Joy tell it, she's not trying to provoke, she's simply drawing on a gift that she was born with.

Joy grew up in a tenement apartment in Brooklyn, surrounded by a large extended family, and she fit in by making them laugh.

BEHAR: I learned all the Shirley Temple numbers.

I would tell jokes.

I was like, uh, the TV.

(laughs).

They wanted somebody to entertain them and I was an only child in this humongous Italian family, so they, I accommodated them, 'cause I guess I loved all the attention.

GATES: They said finally, God sent an act.

BEHAR: She's got an act, the kid, hit it!

GATES: Despite her enthusiasm, it took years for Joy's act to find a wider audience.

After college, she married and tried teaching high school, but found herself drawn to show business.

So she took a job as a receptionist with "Good Morning America" and began to perform standup at night.

Did you draw on your family for material?

BEHAR: Oh, yeah, are you kidding?

(laughs).

First of all, they were funny.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: The women, in particular, were funny, so I always had material like that, I talk about them a lot.

I'm writing plays now, and I'm putting them in my plays.

I keep them alive now, any way, I can.

GATES: Did they like your material?

Did they think you were funny about them?

BEHAR: Yes, they did.

GATES: Oh, that's cool.

BEHAR: They did.

I mean, I don't know, they pretend, I used to be like right in front of everybody, I'd say something... We'd go to a funeral, let's say, a wake, I went to so many wakes, I should have fly, frequent flyer mileage, I went to so many wakes, they dragged me to wakes when I was six years old, seven years old, I'd see dead bodies all done up, nice makeup job, wearing you know, uh, they, they, the corpses were dressed better than they are in the Senate right now.

(laughs).

And I'd come home and we'd have the pasta after the wake, and then I would do 10 minutes on what happened at the wake.

(laughs).

You know?

GATES: Oh, that's great.

BEHAR: And I mean, they would, the, the whole family was like, they would say, they'd hear crazy stuff come out of their mouths all the time.

Like, you know, that we'd be at the wake and they'd say, "Oh, he looks good."

And I was six years old, I said, "He doesn't looked that good."

(laughs).

Or somebody said one time, "He looks just like himself."

Really, who should he look like?

He was a "faccia brutta" yesterday, he's gonna look like Tom Cruise today?

(laughs).

So they, they supplied the material right there at the wakes.

GATES: Despite this wealth of material, Joy struggled for decades to find success as a comedian.

But then one evening she took the stage in front of the legendary Barbara Walters, who at the time was trying to cast what would soon become "The View."

Joy had no idea what was at stake, but her life was about to change forever.

BEHAR: So this friend of mine called me up and he said, "Look, we're doing something for Milton Berle at the Waldorf Astoria, it's his 89th birthday party, could you come up and do 10 minutes?"

GATES: Hmm.

BEHAR: And I said, "Okay," 'cause Milton Berle, I got excited, no money involved here.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: And, uh, I got on stage and I did this whole bit about how, you know, woman, um, a man can get a woman no matter what age he is, no matter what condition he's in.

Like, look at Milton Berle, he was 89, the wife's like 55 or something.

And I made the, um, uh, comparison to Salman Rushdie.

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: Salman Rushdie, who had a fatwah on his head.

They were ready to kill him, he was in hiding for 10 years, he got married three times while he was in hiding.

GATES: Yeah, yeah.

BEHAR: So, I, you know who, who came to the, uh, was it an Avon lady, who was it?

(laughs).

Anyway, I did.

GATES: That's funny.

BEHAR: That bit and a couple of other things, I sat down, I said to my husband, "How did it go?"

He said, "Well, everybody was laughing except Barbara Walters."

GATES: Ooh.

BEHAR: So I said, "Oh, well, who cares?

I'm not gonna work for Barbara Walters."

'Cause it was always an audition to get more work.

GATES: Right.

BEHAR: P.S.

I get a call several months later from the Barbara Walters, uh, people, that they would like me to try out with these other women.

GATES: Huh.

BEHAR: To see if we can do the job, and then I got the job.

GATES: Wow.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: Did you ever ask Barbara why she didn't laugh?

Or what she... BEHAR: She, oh, she said I was studying you.

GATES: Oh.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: My second guest is actor Michael Imperioli, who came to fame as Christopher Moltisanti, the hotheaded nephew of Tony Soprano.

IMPERIOLI: Next time you see my face show some respect.

(gunshot).

(yells).

GATES: Christopher is one of the most iconic characters in the history of television.

But he bears little resemblance to the man who brought him to life.

Michael is calm, self-effacing, and seems incapable of violence even so, I was not surprised to learn that he's long had an affinity for men like Christopher.

Indeed, Michael told me that even as a child, he had artistic interests that hinted at his future.

IMPERIOLI: I started doing, um, writing little, uh, like plays and things like that.

GATES: Yeah.

IMPERIOLI: Some of them were very, uh, dark, actually, even at a really young age.

GATES: Really, like do you remember any of the plots?

IMPERIOLI: Yeah, it's kind of disturbing, I guess I should say it... (laughs).

GATES: Um, I remember, and I didn't perform this for my family though, when I was like, maybe six or seven, there was a movie about prostitutes on TV and pimps and stuff and I wrote a play about it.

(laughs).

I, 'cause I really, it was very fascinating to a little kid.

It's like, what is this is, this world, what is this about, you know?

And from a kid's point of view, it's, you see it in a very limited way.

You don't really understand what it is, but I knew it was dangerous, and I knew there was something very forbidden about that.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Which made me really want to explore it.

GATES: Explore it, of course.

(laughs).

Michael's desire to explore would shape his life, driving him to skip college and head directly to New York City to study acting.

The decision initially seemed unwise.

His classes led nowhere.

And Michael spent years waiting tables struggling to find even small roles, often doubting his own talent.

But eventually, he landed an audition for the part of Spider, a small-time hoodlum in Martin Scorsese's legendary film "Goodfellas"."

HILL: Thank you, Spider.

GATES: And suddenly Michael's fortune shifted in ways he never could have imagined.

IMPERIOLI: They call and said, you know, you got the part.

At the time when you auditioned, all the actors read Joe Pesci's part.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: So, I didn't audition for this character, Spider, I was audit...

I was reading Joe Pesci's lines and I thought, and I had read the book, so I thought I was auditioning for... GATES: That part.

IMPERIOLI: Tommy!

GATES: Right.

IMPERIOLI: So they said, no, you got this part Spider, I'm like, oh, it's just a small little thing in the book.

I was kind of disappointed, you know?

And then I, I realized I'm gonna be acting with Robert De Niro.

GATES: Yeah, right.

How did that change your career?

IMPERIOLI: You know, my teacher Elaine, she always used to say, um, uh, your acting ability will increase exponentially after your first good review.

(laughs).

GATES: I like that.

IMPERIOLI: Uh, and I never really knew what she meant.

But what it really meant was the thing about confidence, like, once you, you do something well, the confidence makes you trust yourself more.

GATES: Michael's performance in "Goodfellas" eventually led to an audition for "The Sopranos."

He's been a star ever since playing a wide variety of roles, both on stage and screen.

But Michael remains best known for his criminal characters.

And as an Italian American, he's well aware of the stereotypes that have surrounded such characters in the past.

In fact, it's his hope that "The Sopranos" help to mitigate those stereotypes.

IMPERIOLI: Before the show got on the air, there was a lot of noise about, oh, another mafia thing... GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Italian American stereotype.

But what happened was, "The Sopranos" is very beloved among Italian Americans.

They really relate to it, they kind of feel like, um, even though they, they, their family might not have been mafia criminals or anything like that, but the family aspect, the food, the culture, the bonds, the ties, the, the characters they relate to.

And it's very, very, very beloved.

And I kind of let that speak for itself.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Like, they don't, you know, they, you may get some people, like, I don't, you know, when I played Governor Andrew Cuomo in "Escape at Dannemora."

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: So before we shot, uh, they arranged for me to meet him.

And the first thing he said to me was, "I've never seen 'The Sopranos.'

My father never watched 'The Godfather.'"

I said, "I know where you're going, and I'm just gonna say, you should watch 'The Sopranos.'"

GATES: Uh-huh.

IMPERIOLI: Because it's a great work of art made by Italian Americans.

And we're all really proud of it and it really, um, has contributed a lot to the culture, at large, and for, you should see that.

And he said, "Fair enough."

♪ ♪ GATES: My two guests both see themselves as products of their Italian roots, but each came to me with fundamental questions about those roots.

It was time to provide them with some answers.

I started with Joy and with the passenger list for a ship that arrived in New York from Naples in 1903.

On board was Joy's maternal grandfather, the very first member of her family to leave Italy for America.

BEHAR: Vincenzo Carbone, 23.

Oh my God, to even think of your grandfather at 23 years old.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: Single.

Occupation: peasant.

Oh... GATES: It's cold.

BEHAR: Nationality: Italian.

Race: South.

What does that mean?

GATES: So the race, they were southern-Italians.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: Different race than the northern-Italian.

BEHAR: Uh-huh.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: I see.

GATES: Okay.

BEHAR: Last residence was Sant'Eufemia, which I've heard of that it was in the mountains somewhere.

Final destination: New York, of course.

GATES: That's the moment your grandfather stepped foot on the United States.

BEHAR: I see.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

BEHAR: Well, you think about, you know, uh, the trek, the traveling that the voyage, he must have been in steerage... GATES: Where everybody's vomiting.

You know, the reason you get seasick is you can't, you lose the horizon.

So there's no horizon in steerage, right?

BEHAR: Oh my God.

GATES: And not exactly luxurious toilet facilities... BEHAR: No.

GATES: Down there, right?

BEHAR: It must've been very rough.

GATES: Vincenzo was likely well acquainted with rough conditions.

His birthplace, the town of Sant'Eufemia was part of Calabria, a region of southern Italy that had long suffered from a power imbalance with the wealthier, more industrialized north.

In Vincenzo's day, it was one of the poorest places in Europe.

And Joy identifies with all that her ancestor did to leave it behind.

BEHAR: You know, the Italians are one of the most patriotic Americans in this country.

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: And one of the reasons is because they were treated so badly in Italy, in southern Italy.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: And, um, I give them a lot of credit, I'm proud of them.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: But, you know, it's not where you end up, it's where you started from the counts, you know, that how far you can go.

And, and they took major risks.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: If you lived in Florence and were "born to the manor" and had money, you didn't have to take a risk.

So I give my grandfather more credit than I, I would give somebody in Florence.

GATES: Yep, so you would've done what he did, which is split.

BEHAR: I would've, I have the spirit in me, that I think that I would've done that.

GATES: Vincenzo eventually settled in a Pennsylvania milltown, but he wasn't done taking risks, in 1907, after just four years in America, he returned to Calabria, where he married Joy's grandmother, a woman named Francesca, or Francis, Zagari.

Then within months, Vincenzo got onto a boat once again and headed back to Pennsylvania, leaving his new bride behind.

BEHAR: He left her in Sant'Eufemia.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: And came back to Pennsylvania.

GATES: And he came back, solo.

So why do you think he left her behind any theories?

BEHAR: Oh, well, he must have come here to get work and he didn't feel like he could support her maybe at first, and he, like a lot of immigrants, they come here from parts of South America, let's say they make a living, or parts of Asia, they, they work hard and then they send for their children, and their children go to college.

I mean, that, that's how it works.

GATES: Sure, or he didn't have enough to pay for the fair.

BEHAR: That's possible too.

GATES: "You stay here and I'll work it out."

BEHAR: Yeah, and "I'll come back and get you."

GATES: I mean, we don't know, but we suspect that your grandparents didn't have enough money to come over together.

BEHAR: It's such a, you know, when you describe their life, it's so hard.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: Such a hard life.

GATES: I mean, hardscrabble, bottom line.

BEHAR: Really, the toughest, toughest.

GATES: After returning to America, it seems that Vincenzo was in fact able to earn enough money to send for his wife.

By 1911, Francis was living in Pennsylvania, and Joy's mother would be born later that same year.

Yet tragically the family's happiness would not last.

BEHAR: Francis Carbone, Occupation: housewife.

Date of Death: October 24th, 1912.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: How sad is that?

GATES: One year.

BEHAR: Death was in Osceola Mills, Pennsylvania.

Acute nephritis.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: Oh, a kidney disease.

GATES: Kidney disease.

BEHAR: So my mother was born in 1912, and that was the year she was, she died.

GATES: Your mother wasn't even one year old when her mother died.

BEHAR: Oh my God, awful.

GATES: And I don't know if you know, but nephritis can be a complication of childbirth.

BEHAR: From childbirth?

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: I did not know that.

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: So my poor mother was alone.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: With her father.

GATES: Mm, did your mother ever talk to you about how losing her mother affected her?

I mean, she was too young to remember it, obviously.

BEHAR: No, she never discussed it, really.

In fact, I didn't know about Francis until I was 17 years old.

My mother sat me down when I was 17, and she said, "Listen, I have to tell you something."

And I thought, what is she gonna tell me?

And then she told me, "Grandma Antonia, who you were raised with is not your biological grandmother.

Your real biological grandmother died when I was born."

Joy told me she believes that her mother never fully processed the loss of her own mother.

And it's easy to understand why within months of Francis's death, Vincenzo took his infant daughter back to Calabria, where she would spend the next 13 years growing up in the world that her father had tried so hard to escape.

Did she talk to you much about that time?

BEHAR: No.

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: She used to tell me things like, oh, yeah, she told me, like she'd, she, she'd make up like stories that were so pathetic.

We'd have, she says, "My father wanted me to learn the piano, and we would bring fruit to the piano teacher," and, like to... GATES: Oh.

BEHAR: Like to bargain with and then she would learn a little bit on the piano because she, they would give, they didn't have money, so they brought food.

GATES: Sure, but that's... BEHAR: Stuff like that.

GATES: But that's smart.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: But sad.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: Did you... BEHAR: But it made you think like, "Oh my God, they had nothing."

GATES: But could she play the piano?

BEHAR: No, not enough fruit.

(laughs).

GATES: We don't know why Vincenzo chose to remain back in Calabria for so long, but it would appear that he never lost his desire to immigrate.

And in 1925, after remarrying, he set all for America one final time, bringing Joy's mother along with him.

BEHAR: Vincenzo Carbone, 45.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: Occupation: A laborer, whatever that is.

Name and address of relative in country, once alien came, wife Antonia.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: That's the step-grandmother.

GATES: Yep.

BEHAR: Where they're going to join a relative or a friend residence, 506 Metropolitan Avenue, Brooklyn.

Purpose of coming to United States: Permanent and Intends to become a citizen: Yes.

GATES: Yes, there's your mother at 14 years of age.

BEHAR: Right.

GATES: Returning to the United States with her father.

What do you think that moment must have been like for your mom?

BEHAR: I think it must have been traumatic.

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: First of all, I'm sure she didn't speak any English at that point.

So I, when I was growing up, she spoke perfect English.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: But as a child, I don't think she did, 'cause there she was in Italy.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: So she comes to this country... GATES: Of course.

BEHAR: She has no way of or no education, they have, still have no money.

The only thing she knows how to do is sew.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: She was incredible seamstress, by the way.

GATES: Hmm.

BEHAR: She would make slipcovers and bridal gowns, and she was incredible.

GATES: Hmm.

BEHAR: But at that age, they put her to work in a factory right away.

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: See, I could start crying now from this, that makes me sad that my poor mother at 14 is thrown into a factory already.

GATES: Right.

BEHAR: She had no chance, no chance.

And, uh, couldn't go to school, there was, you know, no way to go to school.

No way to do a, a life that was really, um, successful, I guess.

GATES: Joy's mother would spend much of her life working as a seamstress in Brooklyn.

But she and her father had nevertheless accomplished something marvelous.

They had transplanted themselves, at enormous, cost to a new country.

And on June 22nd, 1926, Vincenzo crowned that transformation by becoming an American citizen.

So what's it like to see all this effort documented?

BEHAR: It's very touching, frankly.

GATES: And, um, I, you know, I mean, I, I know that I didn't come from, I was not to the manor born, I realize what my background has been, and I feel that I'm standing on the shoulders of people here.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: That they worked and struggled, and here I am.

GATES: But they believed that, that things would get better, that there was a future.

BEHAR: Yes, well, that's what America does.

GATES: Right.

BEHAR: That's the beauty of this country, that it does say to people in these dire circumstances, give me, they say the, the Statue of Liberty, "Give me your tired, your poor."

And they believe it around this world.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: And they come here.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: It's kind of a nice story in a way that America opened its arms to all of these people.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: And it's because they did all this that I can be here.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: That I can have a successful life.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: It's because of what they did, and I appreciate it.

GATES: Much like Joy, Michael Imperioli was about to see how his mother's family struggled to make the transition from Italy to the United States.

The story begins with Michael's great-grandfather, Raffaele Segno.

Raffaele is something of a legend within Michael's family, famed as a patriarch and a community leader who ran a tavern in Mount Vernon, New York.

But the passenger list of the ship that brought him to America describes a man whose future was far from guaranteed.

IMPERIOLI: Age: 19, single.

Occupation: Shoemaker.

I didn't know he was a shoemaker.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Able to read or write: No.

By whom was passage paid: Himself.

Whether in possession of money: $12.

Whether ever before in the United States: No.

Like 19 years old, $12 in his pocket, wow.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

IMPERIOLI: You know, I, I really admire the courage, you know, the courage to, it's a very different world and here now you have access to so much information all the time, so, like, the idea of going to another country, you can go on the internet, look, see what it looks like, you know, even start communicating about job, you know, communicating with people, there's... You were really stepping out into the unknown.

(laughs).

GATES: Totally.

IMPERIOLI: You know what I mean?

You're just hearing word of mouth, what it's like maybe seeing a thing in a newspaper, maybe not.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: I mean, hearing what it's like from other people who have, who have been there.

GATES: Whose cousins have gone there.

IMPERIOLI: Yeah.

GATES: Whose siblings.

IMPERIOLI: It's really kind of incredible.

GATES: Raffaele arrived from Italy on March 26th, 1903.

Though he'd been trained as a shoemaker, he started a new life for himself.

By 1914, he'd married Michael's great-grandmother, a fellow Italian immigrant, and was running his tavern in Mount Vernon, a small city just north of the Bronx.

His brother, Patsy Segno, ran a grocery store next door.

It seemed like the family was living the American dream.

But as we dug deeper, we found newspaper articles suggesting that the situation was a bit more complicated than it appeared.

IMPERIOLI: "Raffaele Segno, 38, is alleged to have fired a shot at Pasquale Tremonte last evening.

The dispute is said to have arisen because Segno's wife's sister, Santa Salzano, and Louis Tremonte, son of Pasquale, Pasquale, have obtained a marriage license, Segno and his wife, he said, "Object to the marriage."

They must have really objected to the marriage.

(laughs).

GATES: Have you ever heard anything about this?

IMPERIOLI: No, I've never heard this.

So my great-grandfather, Raffaele... GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Fired a shot at Pasquale.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Well, I wanna show you a little bit more about this confrontation, would you please turn the page?

IMPERIOLI: Oh, this is exciting.

(laughs).

This is really exciting.

GATES: Michael, this is the same newspaper article we just showed you, only this time we've highlighted a different section.

Would you please read that transcribed portion?

IMPERIOLI: Segno went to see Tremonte yesterday, and they discussed the matter, there were words exchanged, exchanged, Tremonte charges that Segno invited him out into the woods to finish the thing, but he wouldn't go.

Segno is alleged to have then fired a shot at him.

Police officers were shown a hole in the window where the bullet was alleged to have gone through.

Gun could not be found.

Segno gave himself up at headquarters, but denied firing any shot at Tremonte."

(laughs).

So they wanted to go in the woods to like have a, like a dual.

GATES: Yeah, yeah, right.

IMPERIOLI: That was the honorable thing to do, I guess, back then.

GATES: Yeah.

IMPERIOLI: Pistols of dawn or something like that, that's what it seemed like, but, um, I've never, you know, now they must have known, my grandmother must have known this story, but they, I guess this is not something they wanted to talk about.

(laughs).

Um, wow, that's so wild.

GATES: We don't know exactly what motivated Raffaele to shoot at his neighbor.

His objections to the marriage aren't recorded.

But even though it seems highly likely that a shot was in fact fired, Raffaele somehow managed to smooth everything over.

IMPERIOLI: "Family Dispute Over Marriage Is Settled."

(laughs).

"A charge of assault made by Pasquale Tremonte against Raffaele Segno, of 159 West Sixth Street was withdrawn this morning when it was announced, the disagreement had been patched up, and that the men are again friendly.

It was reported a shot was fired, but both men claim they knew nothing of any shot."

It's so Italian.

(laughs).

Because, you know, they settled it within, you know, the family.

GATES: That's right.

IMPERIOLI: Having it public like this was probably very much not what they wanted.

GATES: Oh, no.

IMPERIOLI: And probably not would've happened in Italy.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Because I would imagine the culture there would prefer things to be settled within the family.

GATES: Right.

IMPERIOLI: Um, this is, uh, a taste of what America was like, is that, you know, you do something wrong, it becomes public, they write about it in the paper, they patch it up, things became friendly, God knows what happened and how they patched it up, but, um, settling it within the family, "omertà" nobody talks about the family.

GATES: Nobody talks about... IMPERIOLI: I mean, that was not just the mafia thing, it was, that was, that was the way they, you know, they handled things within communities.

GATES: While Raffaele may have been able to keep the police out of his family's private affairs, he was facing trouble at his tavern that couldn't be so easily resolved.

In 1920, after decades of debate, the 18th Amendment outlawed alcohol in the United States.

And suddenly Raffaele was forced to confront a truly daunting challenge.

How do you think your ancestor fared, all of a sudden, the government took away his business?

IMPERIOLI: I'm assuming, you know, it became a speakeasy, possibly.

I don't know, that's a good question.

GATES: Well, let us turn the page and see.

This is a newspaper article published on February 14th, 1923.

Would you please read that transcribed section?

IMPERIOLI: "Blaze on West Sixth Street."

"There are two stores in the building, one, a grocery store operated by Patsy Segno."

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: "The other, a soft drink establishment run by Raffaele Segno his brother.

This was formerly a saloon.

Shortly after the fire broke out, reports were heard that the blaze was caused by the explosion of a still."

(laughs).

Wow.

GATES: Have you ever heard anything about this?

IMPERIOLI: No, I never heard about this.

GATES: What's it like to read about it in black and white?

IMPERIOLI: Well, they were adapting, right?

They were like, well, they got, I love that they call it "a soft drink establish..." Like they were just making sodas, you know?

You know, um.

GATES: Might that have been a euphemism?

IMPERIOLI: Yeah, right, it's hilarious.

GATES: During Prohibition, many taverns did convert to what were called "soft drink establishments," where people could congregate over non-alcoholic beverages.

But there were also plenty of places that continued to serve alcohol illegally.

And it seems likely that that's what Raffaele decided to do.

According to this article, he and his family were storing liquor in their cellar, which led to a fire.

And this wasn't an isolated incident.

In 1922, Raffaele's sister-in-law, Patsy's wife, was indicted for serving whiskey to a federal agent.

IMPERIOLI: So they did it in the, probably in the grocery store as well.

GATES: Yeah.

IMPERIOLI: You were able to get a glass of whiskey.

Um, wow, wow.

This is fascinating.

GATES: It is, what's it like to learn this?

IMPERIOLI: Um, man, I had no idea.

You know, it's thinking about it now, it's like, it's such an obvious thing, like if you owned a bar and then Prohibition comes, it's like, either you're gonna close it and do something completely different, or you're going to, you know, do it illegally.

GATES: Right.

IMPERIOLI: Right, but this is so fascinating and incredible that this information, that you found this, so wild.

I'm now, I'm, what I'm really curious about is how much like my mother knows about this stuff, like, did she know any of this?

I'm really curious.

GATES: Right.

IMPERIOLI: Because I never heard these stories.

GATES: All told Raffaele's properties were cited at least twice for Prohibition violations.

And in 1924, a federal judge filed an injunction against him.

Yet not only did he manage to keep all these legal troubles from his descendants, it seems that he also overcame them.

Indeed, when Raffaele passed away in 1947, almost 15 years after the end of Prohibition, his obituary describes the patriarch that Michael had long thought him to be.

IMPERIOLI: "Raffaele Segno, who conducted a tavern at 161 West Sanford Boulevard for more than 40 years."

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: "Died today at Mount Vernon Hospital at the age of 62.

Born in Italy, son of the late Ginaro and Josephine Raya Segno.

He lived here for 47 years."

GATES: Yeah, your great-grandfather continued to run that tavern until the end of his life.

What's it like to see that, to think about that great amount of continuity?

IMPERIOLI: Continuity and tenacity.

GATES: Yeah.

IMPERIOLI: You know, and just like not giving in, not giving up and just by, you know, by any means necessary providing.

GATES: Mm.

IMPERIOLI: Um, providing for the family, uh, you know, 'cause that's really what it was about.

It, it wasn't from what I know, it wasn't like they were amassing all these riches... GATES: No.

IMPERIOLI: And properties and things like that, it was really just that's, he had six kids and that's what he did to... GATES: Man was trying to make a living.

IMPERIOLI: Makes me have a lot, a lot of affection for him, more than I, more than I had.

You know, I didn't really know much about him.

GATES: We'd already traced Joy Behar's, maternal roots back to Sant'Eufemia, a town in the Calabria region of Italy.

Joy's mother spent much of her childhood here.

But Joy had no idea that the town had also played a role in her father's family.

The story begins with Joy's paternal grandfather, a man named Philip Occhiuto, and with a record we found in the National Archives.

BEHAR: Philip Occhiuto, my grandfather, age 45, Occupation: Machinist.

"I was born in Sant'Eufemia, Italy on the fifth day of October, 1879."

GATES: That's your grandfather's Declaration of Intent to become an American citizen.

BEHAR: Right.

GATES: But does anything on that record that you just read stand out?

BEHAR: No, this everything is about Sant'Eufemia.

GATES: That's it, Sant'Eufemia, that's the same place your mother's family came from.

Isn't that wild?

BEHAR: Yeah, that is wild.

GATES: Did you have any idea?

BEHAR: No, I wasn't sure where, that they were in the same town, but... GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: Everybody who probably came to my neighborhood in Williamsburg, a lot of them must have been from that, they, you know, they "Come on, I'll get you an apartment."

You know, a lot of that must have gone on... GATES: Sure.

BEHAR: They helped each other.

GATES: Knowing that both sides of Joy's family came from the same town, sent our researchers back to the archives of Sant'Eufemia.

This time to search for records of the Occhiuto's.

It did not take long for our search to pay off.

BEHAR: "The 6th of October, 1879 at the City Hall appeared Sevario Occhiuto, age 28, blacksmith resident in Sant'Eufemia, who presents a baby child, male.

And he declares that the baby child was born at the hours 1:15 on the fifth of the above-mentioned month in the home place in Via Ferrai 15 to Maria Rosa Arena, his wife, spinner resident with him."

Uh, "Lastly, he declares she give him the name of Philipo Bruno," Who was this person?

GATES: That's a record of your grandfather's birth.

BEHAR: Oh, wow.

Philip was born on October 5th, 1879.

His parents, your great-grandparents were Sevario and Maria Rosa.

BEHAR: I see.

GATES: Have you ever heard of those names?

BEHAR: No, I know that Sevario was my uncle, but I didn't know he was named after his grandfather.

GATES: There you go.

BEHAR: I see.

GATES: So now you've climbed another branch of your family tree... BEHAR: Right.

GATES: On this side.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: And there's something else I'd like you to notice on this record.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: Do you see where the family was living when your grandfather was born, the street address?

BEHAR: Via Ferrai.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: 15.

GATES: That's right, please turn the page.

BEHAR: I'll go there when I go to Calabria.

GATES: Look at that.

BEHAR: Oh, look at that, there it is.

GATES: That's Via Ferrai.

BEHAR: Mm.

GATES: The street where your grandfather was born.

BEHAR: Wow.

GATES: That's what it looks like today.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: Now, obviously the houses have been rebuilt since your grandfather's time.

BEHAR: Yeah, well, certainly.

GATES: But, but the size of the structures and the surrounding landscape are all likely very similar.

BEHAR: Uh-huh.

GATES: And look at number 15 on the right.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: That was your family home.

BEHAR: There it is.

GATES: Just across the street is number eight.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: That's a very important address for your family because that's where your mom's father lived.

(laughs).

BEHAR: What?

GATES: Your grandfather Vincenzo was born at number eight.

BEHAR: What?

They were living across the street?

GATES: The families were living across the street from each other.

(laughs).

I mean, just across the street.

BEHAR: I mean, it's almost incestuous what we're talking about here.

GATES: You look out the window and there's an object for your desire right there.

BEHAR: Whoa.

GATES: We don't know whether Joy's ancestors were next door neighbors for a few years or for centuries, there are simply no records to tell us.

But as we poured over the archives in Sant'Eufemia, we uncovered documents that allowed us to trace the Occhiuto's back to Joy's fourth great-grandfather, a man named Saverio Occhiuto.

He was born in the mid-1700s.

That's close to 300 years ago.

BEHAR: Can you imagine what it would must have been like at that time?

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: They've, doctor doctors knew nothing.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: They, they touched things and then touched you and operated on you with dirty hands.

GATES: Right.

BEHAR: There was no cure for diseases, there was no antibiotics.

GATES: They bled people with leeches.

BEHAR: They bled leeches, I mean, and, and they lived some of these, I wonder how long they lived, we don't know that.

GATES: Well, normally if we could find an ancestor from the 1700s, all we ever know about them are their names, right?

BEHAR: Yeah, oh, that's all they ever recorded.

GATES: And the most basic details, like when they were born, when they died, when they married.

BEHAR: I see.

GATES: If we're lucky, we can learn their occupation.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: But unless an ancestor was famous or was from royalty, they didn't leave much of a paper trail behind.

BEHAR: Yeah, they were snobs too.

GATES: So we, so we really don't know much about their lives.

BEHAR: Uh-huh.

GATES: But we learned something very interesting about your fourth great-grandfather Saverio, and I wanna share it with you, please turn the page.

BEHAR: Oh, it's like a mystery evolving... GATES: Joy, this is a newspaper article published in the "Edinburgh Advertiser" on March 25th, 1783.

Would you please read the transcribed section?

BEHAR: Okay.

"The 5th of March, at noon, all the Ulterior Calabria felt an earthquake that lasted six minutes, a thing astonishing.

The shocks were repeated 32 times and lasted until one o'clock after midnight when they felt the strongest.

They continued the sixth and the seventh, the sea raging to break the boundaries of nature and a deluge of water falling from the heavens conspired the destruction of that unfortunate country.

The people enveloped in the thickest darkness saw nothing but lightning, heard nothing but thunder darting destruction and death amidst the tempest through the clouds of 375 villages, which that province contained, it appeared that 320 were lost."

My God.

GATES: This article reads like a novel, but it's largely accurate.

In 1783, when Joy's fourth great-grandfather Saverio was likely in his early 50s, Calabria was hit by a series of devastating earthquakes.

Within minutes, entire towns were reduced to rubble.

You ever hear anything about this?

BEHAR: No, no.

GATES: More than 30,000 people were killed.

BEHAR: Wow.

GATES: And even if you survived the earthquake, you weren't safe because the tremors caused landslides, rockslides, and even tsunamis, one of which alone killed 1500 people who had sought refuge on a beach.

BEHAR: God.

GATES: Let's see what happened to your ancestral hometown, please turn the page.

BEHAR: Alright.

Oh my God.

Well imagine those houses were not built to withstand earthquakes, they're not even today built for... GATES: You got it.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: Joy, this is a newspaper article, would you please read the transcribed section?

BEHAR: "March 11th, 1783, the accounts from Calabria and Messina continue to great, give great alarm here.

On the 6th of March, another violent shock of an earthquake destroyed a number of towns and villages in Calabria that have already been either totally or in great part destroyed amongst the principal ones are Sant'Eufemia."

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: "Exact returns of the mortality have not yet been received here."

GATES: Sant'Eufemia was destroyed in the earthquake.

BEHAR: They must have built some back because they were all ended up there.

GATES: They did, it, accounts indicate that about 945 people, 30% of the population died.

BEHAR: Done.

GATES: And we wanted to see, of course, how Sevario fared.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: But please turn the page.

BEHAR: My fourth great-grandfather.

GATES: Yeah, let's see, please turn the page.

BEHAR: Oh, we're gonna find out, the mystery unfolds.

(laughs).

GATES: Joy, this record is part of Sevario's grandson's marriage record.

It was recorded in Sant'Eufemia on June 9th, 1842.

Would you please read that translated section?

BEHAR: "The undersigned curate archpriest of the Church of Sant'Eufemia, having looked up the book of deaths of the persons who died during the earthquake of the year, certifies the death of Saverio Occhiuto."

Oh, poor guy, he died in an earthquake.

GATES: Yeah, that's a pretty scary way to die.

BEHAR: It's really hard to envision all of this, you know, to, to think about all of this.

This is gonna haunt me.

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: This will haunt me, all this.

GATES: There is a grace note to this story, though Sevario perished, his son, Giuseppe somehow managed to survive.

Giuseppe is Joy's third great-grandfather, and it's difficult to comprehend how he found the strength to keep going.

Could you imagine what it must have been like for him to lose his father and his entire village?

BEHAR: Not, not easy.

GATES: Well, you came that close to not ever being here, because if he hadn't survived, there'd be no Joy.

BEHAR: Yeah.

GATES: Your third great-grandfather.

BEHAR: That's right, his son survived.

GATES: 26.

BEHAR: That's right, I wouldn't be here.

GATES: No, you'd be poof.

BEHAR: Poof.

GATES: Joy, who?

(laughs).

BEHAR: Okay.

GATES: But what's it like to learn this?

To think that you are here today because this ancestor was able to survive in what basically sounds like the apocalypse.

BEHAR: Yeah.

They had hard lives, all of these people, every one of them that's in this book had a hard time.

GATES: But I mean, your survival...

BOTH: Was dependent on, on their survival.

BEHAR: That's right.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: That is correct.

So you come from a hearty stock.

GATES: Yeah.

BEHAR: You know that of survivors.

They're, they're, they're not going to give in.

GATES: Well, Joy, anyone who's watched you for five minutes on "The View" knows that about you.

(laughs).

BEHAR: I guess so.

GATES: We'd already seen how Michael Imperioli's great-grandfather Raffaele, built a life for himself in America, while not always staying within the bounds of the law.

Now turning to a different line on Michael's mother's family tree, we encountered another independently-minded character.

Alberto Luzzi, Michael's maternal grandfather.

Alberto was born in New York City in 1914, the son of Italian immigrants.

He essentially grew up on the streets and his childhood sounds like something out of a movie.

IMPERIOLI: His life as a kid reminded me of like the "Little Rascals" or like "The Bowery Boys," like these, you know, gang of little kids like wandering around Manhattan, getting into trouble and, you know, stealing like cook, you know, pastries and whatever they were doing.

Um, I remember him telling a story about the cop.

There was like the local cops that they were always kind of getting in trouble.

But, um, one of the kids was older, not, not brothers, but some guys that they ran with, and they would actually put, the cop would put the gun down and fight the kid.

Like, that was like how they would kind of resolve like a beef in the neighborhood.

GATES: Uh-huh, huh.

IMPERIOLI: And if the guy beat the cop somehow that would be like, you know, okay, or the idea of that is just bizarre.

Like, that's how they settled stuff in the neighborhood.

GATES: Alberto's troubles largely stemmed from a single source when he was a young boy, his father, Giovanni Luzzi had a job cleaning train cars for what would become the New York City subway system.

It was difficult and dangerous work.

And it led to a, a terrible tragedy.

IMPERIOLI: Certificate of Death, full name John B. Luzzi.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Date of death: April 23rd, 1919.

My grandfather was five, age 38.

Occupation: car cleaner interborough.

Interborough was the subway.

GATES: Yep.

IMPERIOLI: The chief cause of his death was shock.

Crushing of body, contributing causes were dragged by train, accidental.

GATES: Mm.

IMPERIOLI: Mm-mm-mm, I had heard that story from when I was a kid.

GATES: Yeah.

IMPERIOLI: And it always was very disturbing thinking, you know, great-grandfather being, 'cause I knew my great-grandmother, she was alive.

GATES: Mm-Hmm, no horrible way to die.

IMPERIOLI: I mean, yeah, and he was so young.

GATES: Giovanni was struck by a train in the Bronx while working on a stretch of elevated track.

And though the story of his death had been passed on, the details of his life had been forgotten.

We set out to recover them starting in Oriolo, a mountain town in Calabria.

Giovanni was born here in 1879 and likely spent his entire childhood here before marrying and immigrating to America sometime around 1905.

IMPERIOLI: This is fascinating.

GATES: Do you feel a connection?

IMPERIOLI: I do, yeah, um, he, my grandfather always talked about Calabria, which I guess he finally went to when he was an, you know, an adult.

But he used to make, uh, he called it Calabrese toast.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Calabrian toast, which was bread with olive oil, salt, pepper, and paprika.

GATES: Mmm.

IMPERIOLI: My grandmother would make it for him 'cause he didn't cook.

But even something simple like that, he didn't really make much, but, um.

GATES: That was home.

IMPERIOLI: Yeah, I mean, Calabrians uh, he always said this, I'm not making this up, but he always said, um, Calabrians are known for having hard heads.

GATES: Mm.

IMPERIOLI: Hardheaded, stubborn.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Which he certainly was my grandfather, a certainly stubborn, you know, individual, no doubt.

GATES: Like Joy Behar Michael came to me knowing that Calabria has a troubled history and that many of the immigrants who left the region did so to escape poverty.

But as we dug deeper into Giovanni's story, we found something surprising.

His birth record indicates that his father was not a peasant.

He was an attorney.

IMPERIOLI: Unbelievable.

GATES: And you just met your great-great-grandparents.

IMPERIOLI: Who I, I never knew his name.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: I never knew anything about him at all, the fact that he was an, an attorney.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Really kind of shocks me.

Um, and they call my great-great-grandmother, Julia, a "gentlewoman."

GATES: That's right, they were part of the local gentry in Oriolo.

IMPERIOLI: Wow, so a gentlewoman means... GATES: A woman of class, society.

IMPERIOLI: The family had had, had... GATES: Not a peasant.

IMPERIOLI: Had some money.

GATES: Yeah, a lady of leisure is, this is not how you pictured your ancestors back in Italy.

IMPERIOLI: No, I had no idea, no.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

IMPERIOLI: It deepens my pride, which I've always had, you know?

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Of being Italian American and of, you know, my relatives who came here.

And it just deepens that connection and that pride, it makes me want, I, it makes me wanna run to Italy, that's what, that's what I feel like right now.

I feel like I wanna run over to Oriolo in Calabria and just find this street and just look up some people there if I can.

GATES: We don't know why Michael's great-grandfather chose to leave Calabria, given his parents' status.

He likely had a comfortable life in Oriolo and his parents weren't the first in the family to do well.

Moving back two generations, we came to Michael's fourth great-grandfather, a man named Giorgio Luzzi.

Giorgio was born around 1775 and records indicate that he was a farm manager, which means he likely ran an estate for a wealthy landowner.

It was a most desirable position offering an array of opportunities to earn money.

And there was even a saying in Italian from the time, "Make me a farm manager for a year, and if I don't get rich, I'll be damned."

IMPERIOLI: So a farm manager was a thing that was like a thing to a aspire to.

GATES: That's, that's right.

IMPERIOLI: Wow.

GATES: A good thing.

And then you could see, not a surprise, a lawyer would be further down the line, right?

IMPERIOLI: His grandson was a lawyer.

GATES: Yeah.

IMPERIOLI: Amazing.

GATES: But think about this, your Luzzi family, uh, may have not exactly been wealthy, but they certainly had status.

IMPERIOLI: Right.

GATES: In Oriolo for generations, yet your great-grandfather moved to the U.S. to clean train cars, right?

IMPERIOLI: Right.

GATES: Um, but if he hadn't done it, we wouldn't be sitting here today.

IMPERIOLI: I wouldn't be sitting here.

No, and he probably knew that, uh, you know, he was gonna have to be a, do labor... GATES: Sure.

IMPERIOLI: Coming here.

I, I'm sure he wasn't thinking it was just gonna be some smooth, you know, sailing.

GATES: Right, Michael, what does it mean to you to have this history restored?

IMPERIOLI: I've always been, you know, kind of in awe and had a lot of admiration for, you know, the ancestors that I knew about that came here.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: The courage, like we talked about, that it took to come into the unknown, but seeing this other picture and this continuity, especially learning about the life there.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: And it just fills out this picture, you know, that I've had, I've had the same kind of picture in my mind for many, many years and now that's changed for the rest of my life.

GATES: Yeah, big time.

IMPERIOLI: In a very good way, and also for my kids.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: To learn all this, and the rest of my family, who, most of them I'm sure don't know any of this.

GATES: Right.

IMPERIOLI: Um, and never, never would have, so it's, I'm very, very grateful to you for, for, um, enlightening us, it's incredible.

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for Michael and Joy.

It was time to show them their full family trees.

These are all the relatives.

IMPERIOLI: Oh my God.

BEHAR: Oh my God, look at all these people.

GATES: Now filled with the names of ancestors they'd never heard before.

IMPERIOLI: Thank you so much, this is an incredible gift.

BEHAR: This is terrific.

GATES: For each, it was a moment of wonder, offering the chance to connect with long-lost family members on both sides of the Atlantic.

IMPERIOLI: To see these details that we thought were lost to the ages.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: Are here documented, records going back, you know, 200... GATES: 200 years, isn't that cool?

IMPERIOLI: That's really cool.

GATES: Yeah.

IMPERIOLI: It's really amazing.

BEHAR: It means everything to me, it just confirms a lot of the feelings that I have about my heritage.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

IMPERIOLI: I always feel Italian.

GATES: Mm-Hmm.

BEHAR: I mean, I can't wait to bring this book home and show my daughter.

GATES: Mm.

BEHAR: And say, look, this is our family, this is it.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Joy Behar and Michael Imperioli.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots."

Joy Behar Discovers Her Grandfather's Immigrant Story

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep2 | 4m 3s | Joy Behar's grandparents move to America and forge a new life. (4m 3s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S11 Ep2 | 30s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the Italian roots of Joy Behar & Michael Imperioli. (30s)

The Train Accident in Michael Imperioli's Family History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep2 | 4m 2s | Michael Imperioli learns about his maternal great grandfather's death as a train worker in New York. (4m 2s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: